WorldWise readers—

For the small community of journalists whose work focuses on science and global development, David Dickson is not just a familiar name. The late founder of SciDev.Net is a towering figure in the space. His knowledge of each of those topics, and especially where they intersect, was remarkable in both depth and breadth.

I consider myself lucky to know this first hand. It wasn’t long after he hired me at SDN back in 2010 that we began to work together closely, and it became clear this was someone who was both generous with their knowledge and valued each editor for what they brought to the table.

David cared deeply for the Global South. But he had little time for the political talking shop processes that make up much of the global conversation about development, UN top-level meetings included. For me, the jury was still out—I wasn’t convinced he was right on that score.

Years later, with my journalistic attention more firmly turned to those processes, I sometimes find myself transported right back to that office, sharing the scepticism.

Anita

INSIGHT | views & analysis

Time for a reality check.

Like they do every September, last month world leaders flocked to New York City to kick off the UN General Assembly. But this year’s meetings had a special highlight: though organised on the sidelines of the main event, the SDG Summit was one of the focal points.

It even got some coverage outside the usual development-focused media. I’m not sure if that’s a sign of the agenda’s influence or an acute awareness that the world is mostly moving in the opposite direction from that envisioned by the Goals.

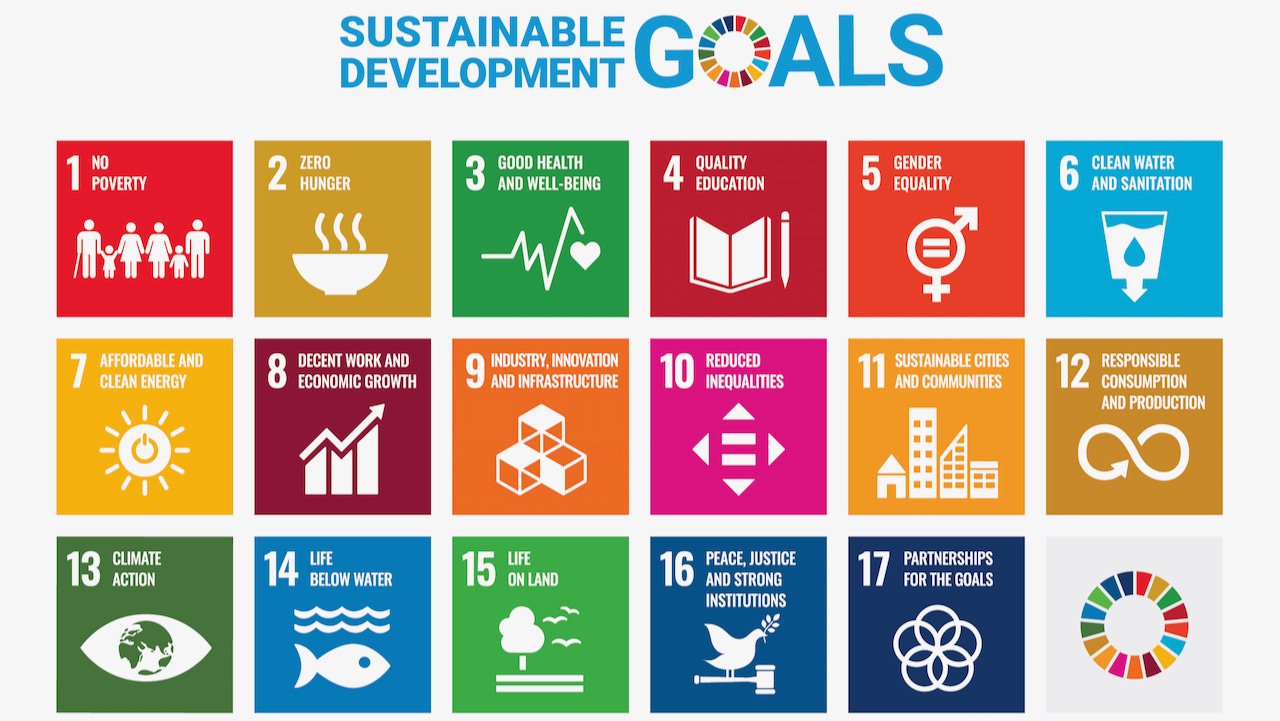

The idea behind the Summit was to jump-start progress towards meeting the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which countries signed up to in 2015 in a joint quest for a healthier, more sustainable and more inclusive future.

It’s a known fact by now that, halfway through the 2030 target year, reaching this version of the future is no longer in sight. Progress towards the SDGs has stalled, and in some cases reversed. Covid-19 and the Ukraine war were the key setbacks, and they’ve reverberated in a number of ways.

The funding needed to invest in meeting the Goals is in short supply or unevenly distributed. Many developing countries are under severe strain from debt. And the UN is struggling to hold on to influence as many nations opt for multilateral diplomacy through different avenues including the newly expanded BRICS. Many prominent world leaders were notably absent this year.

So what came out of the Summit?

I’ve seen hardly any coverage of the outcome. As usual, it’s hard to decipher something concrete or specific among the talk. We do know a political declaration was adopted which reiterates alarm at the lack of progress and reaffirms commitment to meet the Goals.

One part of those renewed commitments that’s new is the Secretary-General’s proposal for an SDG Stimulus of at least $500 billion annually, designed to ease the financing gap for developing countries. Reports suggest this was contested by the US but had the support of European countries—a sign of the geopolitical divisions which are expected to mark ongoing discussions on this proposal.

This is usually the bottom line: wranglings about funding and movement at a g-l-a-c-i-a-l pace.

But the self-imposed 2030 deadline is looming.

Faced with a losing game, what do you do?

Outside these fora, there’s no shortage of opinion on how to start moving the SDGs needle in the right direction. Mostly, that ‘how’ ends up looking like a daunting list of rarely achieved changes to the way governance works—the likes of more cooperation, more finance, long-term planning, integrating the Goals into government and business operations, etc.

Underpinning the familiar suggestions is a widely held conviction that the SDGs are still the world’s best chance to steer itself back on the right path.

It’s tempting to then ‘keep calm and carry on’, as the British slogan goes. But it’s usually the case that things start to get more interesting when we go beyond doubling down on ideas that haven’t worked.

I’ve come across three recent examples of proposals that take that tack to put forward something different.

One comes from a group of scientists led by Frank Biermann, professor at Utrecht University. Writing in the journal Science in the lead-up to the Summit, they called for major reform in how the Goals are implemented, citing evidence of the little political impact they’ve had so far. I find especially interesting the suggestions to introduce a mechanism to make the SDGs adaptable to new challenges, and to turn parts of the Goals into legally binding commitments.

The second is part of the 2023 Global Sustainable Development Report, the independent scientific input to the UN’s SDG process that’s produced every four years. In it the scientists point out that making progress isn’t only about phasing in sustainability—it’s also about getting rid of old unsustainable practices, and this means countries need to actively tackle resistance to change.

The third example comes from Karen Mathiasen, a project director at the Center for Global Development, whose recent blog post point-blank shoots down the suggestion that the Summit’s declaration will be a game-changer. A self-professed SDG-sceptic, she nevertheless concedes the Goals are here to stay. Among her suggestions on how to make progress, what resonates most is the call for more candour about what’s achievable and more specificity about where change can happen.

I leave you with a quote from Mathiasen for a reality-check on the whole process—with which I hazard a guess the late David Dickson would agree.

“Countries pretend to make commitments and the development community pretends to believe them. This expectations/under-delivery loop is implicit in most political documents of this ilk, but in the space between what is promised and what is tenable, cynicism and disenchantment fester. And in the context of widening trust deficits, we need to mind this gap.”

[Sources: WPR + Foreign Policy + Eurasia Review + series of USDN op-eds + Nature SDGs collection + The Conversation + AP News + Devex + CGD]

BRIEFING | around the world

News highlights

In a first, a group of small island nations threatened by rising sea levels and extreme weather have appealed to an international court to clarify countries’ legal obligations to tackle climate change and protect oceans. The hearings were held in mid-September and a decision—which will not be legally binding but is expected to influence future legal challenges—is expected by mid-2024. [Bloomberg + Guardian + The New York Times + CNN + CIEL]

Some 40% of the world’s cargo passes through the Panama Canal, and the Central American country’s rainy season is usually robust—but the region is now experiencing one of its driest periods on record, reducing the amount of water in reservoirs and forcing canal operators to place restrictions on ships using the canal. Already causing shipping delays and forecast to stay in place until well into next year, the restrictions are expected to affect global trade and supply chains. [openDemocracy + WPR]

Brazil’s supreme court has voted against an attempt to prevent the country’s Indigenous communities from claiming ancestral land they did not physically occupy before 1988, when the country’s federal constitution came into force. Campaigners argued this is unfair in part because many Indigenous people are nomadic or were moved by force in the past. The decision is expected to reshape how Brazil treats claims to land. [The Guardian + The Guardian]

A major international infrastructure project to connect India, the Middle East and Europe with railways, shipping lines, high-speed data cables and energy pipelines was announced in early December at the G20 summit. Pushed by the United States to counter China’s growing influence through the Belt and Road Initiative, the project has support from India, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the European Commission. [Axios]

Views of note

Awareness of climate refugees is growing. Full recognition is needed - Cristiano D'Orsi for African Arguments

“The challenge with the Refugee Convention is that it rules out people who are “victims of famine or natural disaster” unless they also have a “well‑founded fear of persecution”.”

Under the radar

Monu Manesar became a social media influencer by streaming his violent attacks - Gerry Shih and Pranshu Verma for The Washington Post

“For a century, vigilantes in north India have worked discreetly in a legal gray zone to protect cows, an animal worshiped by Hindus. But these enforcers have become more extreme and flamboyant in the past decade … Since 2020, the self-styled “cow protection” squad led by Manesar had repeatedly live-streamed its late-night missions to intercept drivers suspected of transporting and slaughtering cows — a job often done by Muslims in India.”

Seeking Solutions

Bolivian start-up produces hyperrealistic prostheses - Roselyne Min for Reuters/Euronews

"People with disabilities in Latin America are different from people in the United States or Europe where the culture makes them accept an amputation and find a functional prosthesis that allows them to go out,” said Riveros. “On the contrary in Latin America, in Bolivia, what people want is to hide their amputations."

The ancient Sri Lankan 'tank cascades' tackling drought - Zinara Rathnayake for BBC Future

“One of the ways that cascade systems reduce drought-risk is by connecting different tanks together, researchers have found. According to a study that measured the changing density of vegetation, tanks that were part of cascades retained more water during the dry season than small isolated reservoirs that operate alone.”

MEDIA | working communications

Our latest MEDIA post featured a dispatch from Zürich, where until mid-October the open-air installation Open Your Eyes brings photography and science together to sensitise the public about the SDGs.

Also note an earlier project, by photographer Nick Danziger, which focused on the previous incarnation of the UN’s global goals, the MDGs or Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Danziger had begun to document the lives of women and children in eight low-income countries in 2005—and he returned 10 years later, as the MDGs were running their course, asking if those goals had made any difference to their lives. The work can be seen in the book Another Life.