'People just walk into the desert, and vanish'

🌐 A conversation with filmmakers Lisa Molomot and Jeff Bemiss.

VIEW

Analysis and global perspectives in health, development, planet.

Slowly and quietly, climate change ups the stakes.

Migration tends to grab the attention of media and the public when it happens suddenly and dramatically.

But most of the time it happens slowly and quietly. And the toll it takes is often invisible.

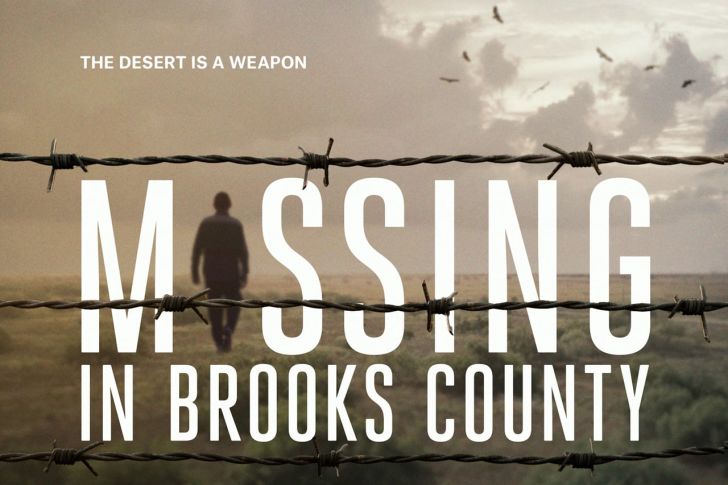

The US-Mexico border is one place where tragic migration stories have been unfolding for years. You might want to look away—but in the eerie first few minutes of their film, Missing in Brooks County, Lisa Molomot and Jeff Bemiss bring you face to face with the reality of what that looks like 70 miles north of the border. It marks the start a journey where we meet the people touched by it—families, activists, locals, scientists—and get a sense of how a tense migration debate plays out in this part of the world.

The problem is not new. A US policy of ‘Prevention Through Deterrence’ has been criticised for its role in migrant deaths along the border for some time.

But the impact of climate change is making things worse on two fronts. It’s already pushing up the numbers of people crossing Central America and through Mexico to the US in search of a better life; the trend is set to continue. And at the border, extreme heat and lack of water make it more likely that dangerous crossings through desert will cost lives. (Human Rights Watch + CNBC + CBS + Carbon Brief + Popular Science)

Supplying water becomes an almost radical act in Brooks County, where co-directors Molomot and Bemiss spent years filming to tell this important story. Our interview is part of a series of conversations that get behind the scenes of some of the filmmaking featured in this year’s Global Health Film festival.

You can watch the full interview here—what follows is an excerpt, edited for brevity and clarity.

AM: What is the film about, briefly?

LM: Our film is about Brooks County, Texas, where many people end up dying due to the temperatures, due to a lack of water. The reason why this is all happening is there's an interior checkpoint 70 miles north, not on the border—the border of Texas is a river. Our film follows two families looking for their loved ones who went missing in Brooks County. It [also] follows other people involved in this crisis.

How easy was it to make connections with the people featured in the film?

LM: It's an interesting story, how we met the Romans, the main family featured in our film. We had already been filming for a year and a half, and created this very simple website for our fundraising purposes. Someone in the Roman family [searching] for Homero, who is the missing loved one in that family, was Googling missing in Brooks County. She came upon our film’s website, and she reached out to us. Their story was very compelling. They also had a lot of materials from the time that he went missing, like calls from border patrol, calls from the smuggler. And they were willing to participate. We really connected with them. Their story actually became the main story in our film.

We kept going back [to Brooks County] again and again, asking people over and over for their participation. It's a process. People in Brooks County are really used to having media visit, they're used to people coming for a day or half a day and getting the story and leaving. We just kept coming back. I think that really helped us build the trust and connections. We were really upfront with people about what we were doing. And I think they probably appreciated us really digging into this story. People seem to be pretty supportive of the project.

I'm slightly surprised by that—I would have expected some resistance as it’s an issue that has conflicts and politics attached to it.

JB: It took us about three years of asking and sort of nagging to get invited out on one of those nighttime operations [with vigilante group Texas Border Volunteers]. Overall that group was pretty open to the media, but only to a point, and I just think it took time to build trust.

How many years did the whole project take?

LM: We started filming in January of 2015.

JB: It was interesting filming through three presidential administrations: Obama, Trump and Biden.

How did that manifest itself in your process, in your experience?

LM: Well, in some ways, nothing changes from President to President. Definitely, during the Trump administration, there was more law enforcement around the checkpoint which forced groups [of migrants] to be dropped off further south—which made the walk longer, which obviously makes it more dangerous. But overall, the important thing that people have to know is that this problem is getting worse for a number of reasons. In essence, things don't change from a Democratic president to a Republican. It's the same situation, which is people are dying.

What we're talking about is the number of migrant deaths since ‘Prevention Through Deterrence’, this policy that started in the early to mid 90s under the Clinton administration. Since then, there have been many migrant deaths along the border in Arizona, in California. Now, Texas is the place where most of the migrant deaths happen. But [in Brooks County], the situation was the worst this past year than it's ever been along the border. Because of climate change, people are fleeing their homes, temperatures in South Texas and Arizona are hotter than ever, in the summer. I think this situation is just going to continue to get worse and worse until people really look at this strategy and try to do something that would make our border more humane.

Have you seen signs of a change in attitudes? What has been their reaction from people who have watched your film?

JB: We had a screening for the border patrol—they actually responded pretty positively. And they're talking about perhaps showing it more widely within that organisation. We're now working on a legislative screening: we have a member of Congress who is going to set up a screening for congressional colleagues in [Washington] DC. We're really excited about that. It will be a process, obviously. Most Americans don't know that this is happening. It's hard to believe that this could be happening on American soil as a deliberate result of a policy. Raising awareness is a big part of what we're trying to do with the film.

Any other plans coming up in terms of screenings?

LM: We have a lot of international screenings coming up, particularly in Mexico this Spring—visit our website [for] a whole calendar. And then we are going even wider [with] screenings in Berlin and Hong Kong, and Paraguay. And the film is streaming on all the usual platforms now. But, we're going to continue to have impact screenings, community screenings. We want to perhaps reach a more Conservative audience—reach people who may watch this film and think about the things they're saying about immigrants, or think about perceptions they had about immigrants. We want this policy to change, but we also want to have a different conversation around immigration in this country.

Are you aware of other efforts or advocacy to change policy?

JB: Lisa and I have been on so many calls where the people advocating in this space, they talk about the fact that there's always something louder and more urgent that comes along. I mean, if this death toll were the result of something like a war or genocide, we couldn't ignore it very easily. But migration is very unusual—it's quiet, it's invisible. People just walk into the desert, and some of them vanish. And it's very hard to create the sense of urgency that would create the political will to address this.

LM: But a bill that was passed in December of 2020 [The Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains Act] is the first time ever—since ‘Prevention Through Deterrence’, since the early 90s—that our government has acknowledged their role in these deaths. That was pretty significant. And that was signed by Donald Trump actually! We're hoping that our film can demonstrate to Congress the need, and who the money should go to. It's not going to prevent migrant deaths from happening, but it is a step in the right direction.

🎥 Find out where to watch Missing in Brooks County

➖ Support the South Texas Human Rights Centre

📩 Get updated about future Global Health Film events

Briefing Highlights

TREND TO WATCH

As Russia’s war on Ukraine continues, we’re starting to see the picture of its impact on the rest of the world in finer grain. Here are a few snapshots, focusing on poverty and humanitarian aid:

Price spikes are expected to push over 40 million people into poverty;

The crisis is expected to deepen the impacts of drought in the Horn of Africa, which is facing its driest conditions in more than 40 years;

In the month or so since the war began, an additional 23 million people have been short of food, according to the World Food Programme

…which expects its costs for a humanitarian response to rise by approximately US$850 million this year;

Humanitarian agencies will need funding to respond, but this may come at the expense of responding to other crises.

UNDER THE RADAR

After 18 months of negotiations towards an agreement to waive patents to Covid-19 vaccines, there’s a provisional deal on the table negotiated by South Africa, India, the EU and the United States. If agreed, countries would be eligible to issue a single authorisation waiving intellectual property rights to multiple vaccines if they have exported less than 10% of the global supply of vaccines—that’s everyone except China, the U.S., and the EU. Predictably for a compromise deal, it’s being criticised by both advocates and pharmaceutical companies.

Based on Briefings published March 22 + March 29

—

COVID-19 PANDEMIC

WHO: Omicron subvariant is now the dominant strain worldwide - Axios

The looming Covid-19 treatment equity gap - Devex

UN analysis shows link between lack of vaccine equity and widening inequalities - UN News

Will ‘open-source’ vaccines narrow the inequality gap exposed by Covid? - FT

ENVIRONMENT

Water supply fears as Morocco hit by worst drought since 1980s - East African

Deforestation on the rise as poverty soars in Nigeria - Humanitarian News

A drowning world: Kenya’s quiet slide underwater - Guardian

HEALTH

Tiny particles of plastic have been detected in human blood for the very first time - Fortune

Brazil reports a 35% increase in dengue cases in first two months of 2022 - Outbreak News

A first-of-its-kind study looks at global abortion rates - US News & World Report

SOCIETY & DEVELOPMENT

Ukraine war and pandemic force a retreat from globalization - NYT + FT

Another journalist shot dead in Mexico, eighth so far this year - Al Jazeera

Taliban suddenly backtrack on pledge to open schools for all girls - Axios

HUMANITARIAN

Looting and attacks on aid workers rise as hunger adds to unrest in South Sudan - Guardian

Beyond Ukraine: Eight more humanitarian disasters that demand your attention – TNH

From the week’s global soundtrack 🌐

✔️ Independent and reader-funded

🤍 Liked this WorldWise email?

Tap the heart button. Forward to a friend. Comment or reply. Follow on Twitter.

📩 Help keep WorldWise going

If you support global journalism, please consider a subscription or one-time donation.