Health at COP28: progress or ‘healthwashing’?

Welcome visibility could also be a distraction 🌐

WorldWise readers—

I have two thought bubbles to share today.

One has to do with the war in Gaza. To say it’s hard to watch what’s unfolding there in humanitarian terms is an understatement. But here I’ll focus on something else, through the words of Guardian columnist Nesrine Malik: “Trust in the ‘international community’ will never be the same”, she writes in an opinion piece. It resonated with me. I feel and fear that she’s right.

On to health-related affairs: last month I wrote a piece for The Lancet, about a recommended policy focus on cleaning up spices as a cheap and easy way to move the needle on ending childhood lead poisoning. This was made by an expert panel convened by the Center for Global Development, based on evidence of a successful crackdown on adulterated spices in Bangladesh (and then Georgia), much of which is led and documented by research scientist Jenna Forsyth.

I picked up on the story in part because it’s unusual to see a clear path to an ‘easy win’ for a public health problem that has been with us for decades, and is almost forgotten.

On that note: toxic pollution was once the central theme of environmental health concerns. Nowadays the spotlight is on the climate, even as pollution problems remain unsolved.

In the case of air contaminated by burning fossil fuels, the two overlap.

Anita

VIEW EDITION | insight and news for a rounded take on global affairs

INSIGHT | views & analysis

The health sector is having a COP moment.

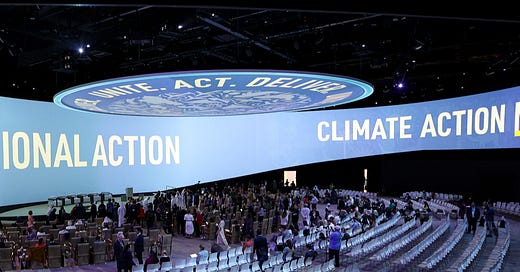

For the first time in the history of UN climate summits, this year included a dedicated Health Day which took place last Sunday, December 3rd. There was also a first-ever Health Ministerial meeting. At least 200 officials from about 90 countries RSVP’d for the meeting, according to some reports, though developing country representation appears mixed.

Sidenote: there was, in fact, a health-related commitment at COP26, which 78 countries signed up to. You might say that was the real ‘first’ for the health sector at the climate COPs. Still, many observers see this year’s strong official presence as a signal that the link with climate change is finally being acknowledged by negotiators.

Dr. Sultan Al Jaber, the controversial COP28 President, has said that “the link between climate change and health is becoming increasingly evident every day”.

Many health professionals are energised by this year’s inclusion in official proceedings. And they’re highly aware of the stakes. In the runup to the event, millions signed an open letter to the COP28 presidency and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) call to action. There was a third letter, by the Global Climate and Health Alliance. All of them called for a phase-out of fossil fuels as a priority.

And that’s where the rubber meets the road.

But before we get to that—let’s briefly revisit what’s at stake.

In short: “the very foundations of human health”, according to the latest Lancet assessment on the topic, which was published in mid-November. Most COP-related media reports cite this assessment for the latest on how climate impacts our health—skip ahead if you’ve seen the details.

—

The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

A total of 114 scientists and health practitioners from 52 research institutions around the world looked at the evidence and highlighted the following risks on the horizon:

HEAT—Heat-related deaths of people older than 65 years of age have increased by 85% since the 1990s. If global temperatures continue to rise to just under 2°C—as they are currently on track to do—the number of people dying each year from heat-related causes is expected to spike by 370% by midcentury. Globally, exposure to extreme heat leads to reduced productivity or inability to work, and this may have led to income losses up to $863 billion in 2022 alone.

INFECTIOUS DISEASE—Warmer conditions are putting more people at risk of serious infectious diseases such as dengue, malaria, and West Nile virus. The distribution of these diseases is also affected by other climate-related changes such as increased drought, rising sea levels, and reduced access to clean water. We still don’t undestand the impact of changes in the timing and routes of migratory birds, which carry pathogens across continents.

FOOD INSECURITY—As high temperatures and droughts destroy crops, more people are losing access to safe and nutritious food. In 2021, an estimated 127 million more people experienced moderate or severe food insecurity linked to a higher frequency of heat waves and droughts, compared with 1981-2010. Extreme weather can also mean less work for people who make a living outdoors, and losing income means struggling to afford food.

AIR POLLUTION—Of more than 8 million deaths worldwide from outdoor air pollution, 61% are linked to fossil fuels. Asia bears the brunt, with 77% of all deaths linked to particulate air pollution. The health impacts, such as heart disease, cancer and neurological disorders, persist in every region, but especially in cities.

—

All this is costly in terms of $ too.

By 2030, according to some estimates, that cost to health systems is projected to reach between US$2-4 billion. The more negotiators postpone action, the higher those costs are expected to be.

Maria Neira, the WHO’s climate chief, also argues that the actions needed to cut carbon emissions—encouraging walking and cycling, for instance, or supporting people to shift to sustainable and healthy diets—will also bring health benefits that go beyond those directly linked with preventing climate impacts.

Overall, according to the agency, those benefits trump the costs of mitigation.

But the message doesn’t seem to be getting through.

That’s despite some progress. About 90% of “nationally determined contributions” or NDCs, the jargony term for national plans to meet Paris Agreement goals, now include health considerations—up from 70% among the countries that reported NDCs in 2019. The WHO is also seeing more health-inclusive and health-promoting climate targets and policies.

Still, health remains underfunded. Just 10% of national plans include domestic funding for health; 20% of countries’ long-term strategies make provisions for funding the sector with measures such as taxes or carbon pricing mechanisms; and health-related projects currently receive between 1% and 2% of adaptation funding, and 0.5% of multilateral climate funding.

So, will this year’s COP presence make a difference?

The COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health has now been endorsed by 123 countries. It officially recognises the growing health impacts of climate change for the first time. And it includes commitments for new finance to boost health systems and scale up solutions—including $300 million by the Global Fund and $100 million by the Rockefeller Foundation.

This is along the lines of what was expected, in terms of a boost in financing. A positive step, impact yet unknown.

Another statement from the declaration caught my eye. Referring to countries’ commitment to better integrate health and climate policies, it specifies that this will be done in part by:

“Taking health into account, as appropriate, in designing the next round of nationally determined contributions, long term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications.”

Why this matters goes back to rumblings of discontent about the document.

In the lead-up to COP28, Maha Barakat, UAE Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs for Medical and Life Sciences, who is one of the parties behind the declaration, emphasised the need for the healthcare sector to adapt—where ‘adaptation’ in this case seems to conflate the ideas of becoming more resilient to impacts, and curbing emissions.

The problem with that last part is proportionality: the health sector accounts for just 4.4% of global emissions.

Overall, Barakat’s statements can read as a placing of responsibility on the sector to mitigate, rather than acknowledging what the surging burden of ill-health really means—both in terms of the cause, and the resources needed to deal with it.

Richard Horton, the Lancet’s editor-in-chief, spelled this out in a Devex interview:

“There is a real concern that the whole of COP 28 is going to focus on adaptation, and dodge the bullet, so to speak, about mitigation.”

From this point of view, it’s not difficult to see the framing of this year’s celebrated formal inclusion of health as problematic. Three reasons why:

One—adaptation is necessary, but it’s limited.

In the words of Jeni Miller, head of the Global Climate and Health Alliance (GCHA), who spoke to Health Policy Watch:

“We do need greater investments in our health systems to adapt to the impacts we are feeling across the world. But we are currently feeling large health impacts at 1.1 C [of warming] in terms of extreme weather, heat and disease, while we are on track to hit 2.8 C. So we just don’t have the capacity to adapt to the level of warming that we are currently projected to hit based on the policies being implemented.”

Two—health is still being kept at arm’s length of the negotiating table.

According to Ramon Lorenzo Luis Guinto, director of the planetary and global health program at St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine in the Philippines, who spoke to Grist:

“I sometimes describe the health sector as the newest kid on the block when it comes to the climate discourse. We still can’t enter the negotiating room. At the end of the day, health is on the side.”

Three—is this actually ‘healthwashing”?

Not my expression, but that of Horton—see earlier comment about concerns that COP28’s focus on adaptation will come at the expense of mitigation objectives. The journal’s stance on that has been clear for a while: its 2022 climate and health report was subtitled “health at the mercy of fossil fuels”.

So should this year’s focus on health count as progress, or is there a “danger of healthwashing” as Horton put it?

It’s certainly been the case so far that the summit has seen a sideshow of positive moves: a widely celebrated agreement on a ‘loss and damage’ fund on the first day, and dedicated ‘days’ that highlight climate links with food as well as health, both issues that were previously sidelined.

But it’s the negotiations to phase out fossil fuels that’s the main event. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario (or even a strategy) where the sideshow serves as a distraction from a potentially less celebrated outcome on that front. Time will tell.

The way I see it, if your goal is to delay a fossil-fuel phase-out, letting health into the negotiating room could be dangerous. Because if it were allowed to sink in—what climate change will mean for the daily function of all of us, and for the future cost of living well in a drastically changed planet—then it gets that much harder to escape the imperative to act.

[Sources: Health Policy Watch + Lancet + Grist + Planetary Health Alliance + Devex + NYT + Axios + Nature + Science + Guardian + WHO + Health Policy Watch + UN Brief]

BRIEFING | around the world

News highlights

While the war in Gaza has grabbed global headlines, for good reasons, media attention is largely missing for other conflict hotspots. A few reports have highlighted the civil war, ethnic cleansing, hunger and massive displacement underway in Sudan. In the seven months since a long-standing ethnic conflict got reignited, nearly a tenth of the country’s population—4.5 million people, which is three times the combined number of people living in Israel and the Palestinian territories—have been forced out of their homes, 1 million more fled to neighbouring Chad, and thousands have been killed. There are reports of sexual and gender-based violence, including abductions leading to slavery and forced marriage. But humanitarian aid for some 25 million people remains underfunded, and there’s little political attention. [Vox + Economist + WaPo + Al Jazeera + Guardian + OHCHR]

The COP28 climate summit kicked off with a surprise move: the formal adoption of a 'loss and damage' fund, which has been in the works for years. The fund is to govern financing for reconstruction in vulnerable nations facing the worst of climate impacts, and is a form of compensation by high-income countries. The agreement came earlier in the proceedings than anyone expected, with pledges of more than $400 million including $17.5 million by the United States, which has historically opposed the fund. Some details remain unclear, including how the money will be distributed and whether poorer nations will need to repay it in the future—not an insignificant detail. Another concern is whether the fund can dispense to right places fast enough. Countries had finalised a blueprint for the fund in early November, with one key compromise by NGOs and developing countries: agreeing to temporarily house the fund at the World Bank for the first four years—an issue that boils down to who controls decision-making. [Nature + Guardian + The Hill + The Guardian + The New Humanitarian + Devex + African Arguments + CGD]

Talks on a legally binding treaty to reduce plastics pollution ended without a consensus in November. More than 1,000 delegates from 175 countries gathered in Nairobi to agree details of what is expected to become the first international treaty governing plastic pollution, due to come into effect by the end of 2024 after five rounds of negotiations. This was the third round, which centred around a “zero draft” of a possible agreement that contains proposals ranging from reducing production and ambitious global bans on single-use plastic packaging on one end of the scale, to voluntary measures decided by each country to encourage reuse on the other end. The next round of talks is due to take place in April. It’s worth noting that the number of lobbyists equalled that of all delegates from the 70 smallest UN member states taking part in the negotiations. [AP + Devex + TIME + Chatham House]

The rollout of malaria vaccines is being scaled up in high-risk parts of Africa after a pilot phase in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. The first shipments have reached Cameroon in a historic step towards widespread vaccination against one of the deadliest diseases for children in this part of the world. RTS,S is the first malaria vaccine to be recommended by the WHO. Vaccinations in the pilot phase led to a substantial drop in severe malaria illness and hospitalisations since 2019. The vaccine is to become part of routine immunization programmes, with the first doses set to be administered starting in January 2024. [Barrons + Africanews]

Pakistan has gone ahead with its plans to deport undocumented Afghan migrants—and reports point to similar moves in additional countries. More than 100,000 Burundian refugees are facing forced removal from Tanzania. Libya is deporting hundreds of undocumented Egyptian migrants. And South Africa is planning to temporarily exit the UN’s refugee conventions to tighten up restrictions, including potentially passing new laws paving the way for removing some refugees to other countries. There are similar moves underway in Europe, including by the UK and Denmark. [Foreign Policy + Africanews + Telegraph + Reuters]

Point—Counterpoint

“MrBeast”, a YouTube sensation with over 200 million followers, recently published a 10-minute video about one of his projects: building 100 water wells in villages across Africa. It attracted over 120 million views and was praised for highlighting water scarcity, as well as countries’ failure to address it.

But not everyone is a fan—here are two arguments for and against his initiative.

“In many cases, the reality of this type of international development from philanthrocapitalists has little to do with the sustainable development of local and rural communities in Africa, and everything to do with the social currency of audience commodity and white saviorism.”

🔗 Why YouTubers engaging in international development is dangerous - Jacob Stewart for Devex

“MrBeast might profit from the number of views, new African subscribers, and even improve his philanthropy image. The fact is, he is providing a vital aspect of life, where many local African governments have failed.”

🔗 Why canceling YouTube's MrBeast after building 100 wells in Africa is not smart- George Okachi for DW

Under the radar

“During a recent visit to several communities in northern Israel, dozens of activists The New Humanitarian spoke to described still feeling a pervasive sense of dread. But they were once again mobilising to try to salvage and carve out space for a vision of a more just and inclusive Israeli society for Jews and Palestinians.”

🔗 In Israel, joint Jewish-Palestinian efforts look to salvage vision of a shared society - Eetta Prince-Gibson for The New Humanitarian

Views of note

“Unless biodiversity markets are well designed, there is a risk they will become conservation doublespeak, legitimizing biodiversity destruction for economic gain while purporting to promote biodiversity conservation.”

🔗 Biodiversity market doublespeak - Michael J. Vardon and David B. Lindenmayer for Science

Against the grain

“There’s a 50/50 chance—a coin flip—that another pandemic on the scale of COVID-19 will occur in the next 25 years.”

🔗 How big is the risk of epidemics, really? - Swati Sureka and colleagues for the Center For Global Development

📢 Want more global news updates and media opportunities?

MEDIA | working communications

ICYMI—Our latest MEDIA post featured an interview with Gerri McHugh, director of Global Health Film, with a preview of this year’s festival. Online screenings run until the 10th of December, so there’s still time to tune in (details here).

![The Health Day Opening Session at COP28 [credit: UNclimatechange] The Health Day Opening Session at COP28 [credit: UNclimatechange]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!baA5!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F26eb7fa1-55f7-4934-99bc-a4ea4135dec7_1280x480.jpeg)